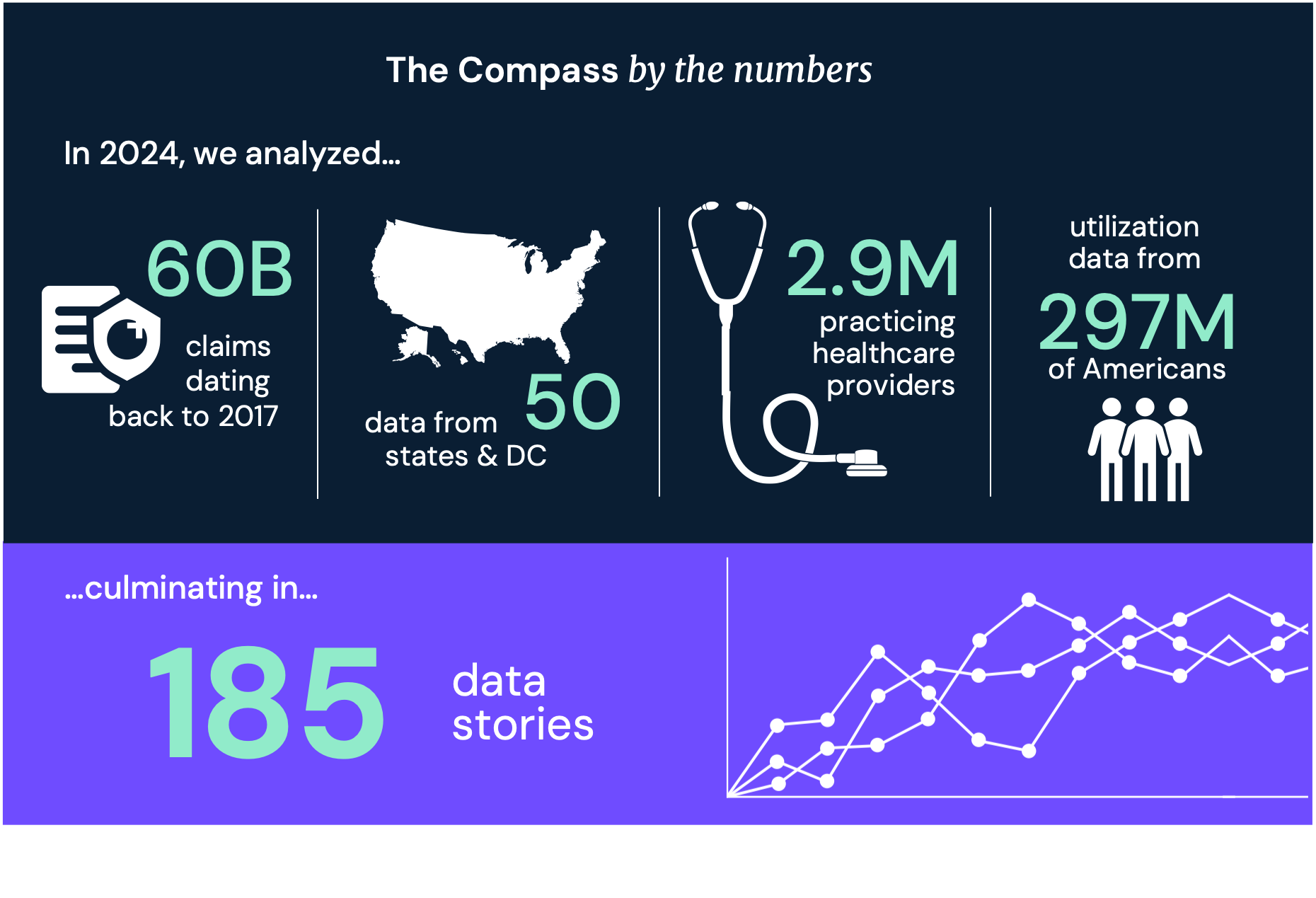

A year ago this week, I started writing The Compass with the intent of sharing data-driven insights to help industry leaders better navigate the increasingly complex and competitive health economy.

As the readership has grown to include more decision makers across more segments of the health economy, many have asked why I started The Compass.

Improving the speed and quality of decision making among every healthcare stakeholder has never been more critical. Yet, the disproportionate amount of data stemming from the health economy makes it even more difficult for stakeholders to gather, analyze, and interpret the data in a meaningful way to inform decisions.

Having trained with many of the nation’s leading health economists and health policy experts, I have seen first-hand how their research influences developments to U.S. healthcare. In my work with senior executives of the nation’s largest health systems, health services, and supplier organizations, I have observed a lack of sufficient data-driven information behind industry decisions.

Narrowing the gap between peer-reviewed research and industry anecdotes (often based on small-sample surveys or media headlines) has been a career-guiding ambition. The Compass was born out of a desire to publish academically rigorous research in the form of data stories that can help guide industry decisions.

With that in mind, here are some reflections from the data stories written over this past year:

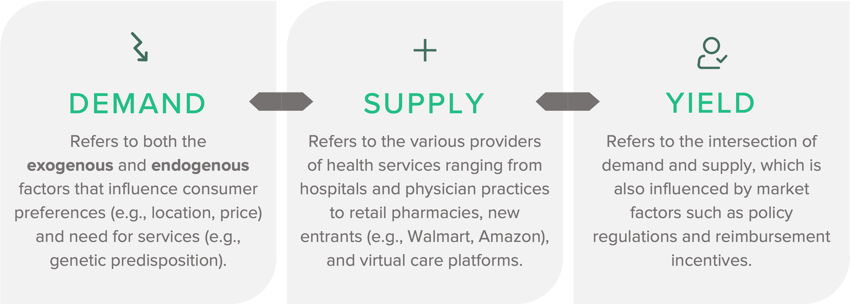

For decades, the U.S. health economy has operated as if the fundamental rules of economics – demand, supply, and yield – did not apply. Many of our analyses have unveiled how present the laws of economics are in healthcare. For example, telehealth proved not to be substitute good for in-person care, except for instances of Behavioral Health.1

Over this next year, these economic principles will continue to guide and shape our research questions, bringing additional rigor to our data stories.

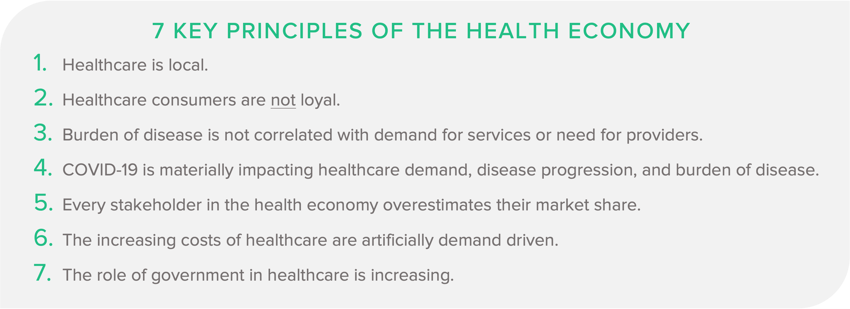

While we have only scratched the surface in identifying the data-driven trends shaping the health economy, these key principles remain evident:

1. Healthcare is local.

Most healthcare veterans know that healthcare is local and, therefore, “know” that demand for healthcare services varies between markets. While national or even state-level incidence rates help reflect the health status of a broad population, incidence rates within a locality (e.g., ZIP Code, county) more precisely reflect demand in an individual market. As a result, strategic initiatives (e.g., physician staffing, therapeutic distribution) must consider inter- and intra-market differences to effectively meet the care needs and preferences of individual consumers.2,3

For example, the national increase in primary care utilization by females ages 20-49 varies significantly by market. Several factors influence primary care utilization at the market level, including provider supply, disease burden, and population migration.4

2. Healthcare consumers are not loyal.

Every healthcare consumer is biologically, demographically, and behaviorally different. Just like consumers tend to have multiple streaming subscriptions (e.g., Netflix, Hulu) and buy groceries from more than just one store brand, healthcare consumers "split" where they receive care across an average of 4.2 provider networks. Contextualized differently, U.S. healthcare consumers are 60% loyal to consuming services within a single provider brand or network.5 Previous analysis revealed that consumer loyalty has decreased in some markets while maintained steady or slightly grown in others.6

As consumers continue to have abundant choices for healthcare services – ranging from longstanding providers (e.g., health system) to new virtual and primary care players to new retail entrants (e.g., Walmart, CVS) – earning the consumer’s loyalty will become increasingly difficult for every provider brand.7,8,9 Notably, prior analysis suggests that even some of the largest health systems delivered care to more than 21% of the consumers in their market.10

3. Burden of Disease Is Not Correlated With Demand for Services or Need for Providers.

No two health systems, markets, or facilities will experience the same demand curve, irrespective of a general increase in burden of disease at the national level. While it is true that the burden of disease is increasing, it is merely one component underlying demand.11 Research shows that annual inpatient admissions have declined by 3.5M from 2008-2016 while the number of hospitalists has nearly doubled in that time.12 Whereas much of the physician shortage discussion has been grounded in the assumptions of population growth and aging demographics, we must remember that demand for services is primarily a function of care trends and population shifts, each varying in its impact at the market level.13

4. COVID-19 Is Materially Impacting Healthcare Demand, Disease Progression, and Burden of Disease.

With Americans delaying, and in many cases foregoing, preventive and acute care for an extended period due to the COVID-19 pandemic, an increasing burden of disease is likely, reflecting an inverse relationship between burden of disease and demand.14 Prior research compared demand projections with and without the effect of the pandemic. The data suggest that the pandemic not only increased demand for certain downstream services but also shifted the underlying reason for the increase (i.e., incidence in disease rather than demographic variables).15 Healthcare stakeholders must look beyond their own learned experience to understand the level of impact the pandemic will have. Logic suggests that capital market activities by established stakeholders with robust data and analytics capabilities are useful to identify emerging trends, and monitoring activity in different sectors of the health economy allows stakeholders to identify product, service line, and partnership opportunities to inform investments in growth strategies.16

5. Every Stakeholder in the Health Economy Overestimates Their Market Share.

A common misconception is that healthcare supply is going down, and demand is going up. Healthcare stakeholders not only overestimate their market share but also fundamentally misunderstand the market forces that determine market share. As a result, they are incapable of predicting the future. One example of this sentiment was observed in our telehealth research. The fact is telehealth suppliers are competing for a smaller share of the population than was originally anticipated. Both traditional health systems and new retail entrants must not only discern who their current users are in order to retain patient volume but also identify consumer segments they have not yet reached. While investments in tele-enabled companies will continue to grow and the number of niche suppliers increase, demand in the overall telehealth market continues to shrink.17,18

6. The Increasing Costs of Healthcare Are Artificially Demand Driven.

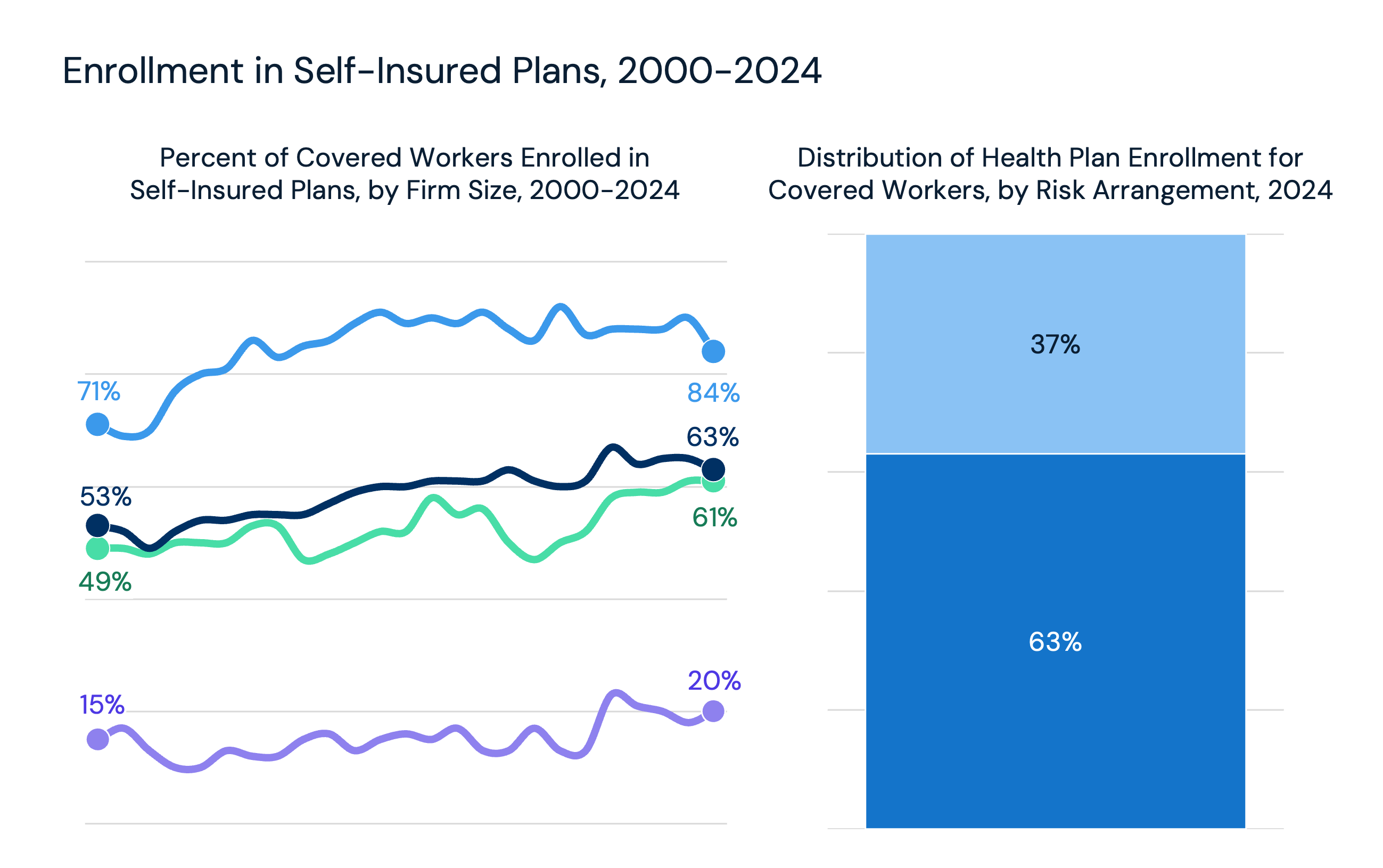

As more suppliers enter the care delivery market, a greater number of providers will be competing for an even smaller share of “target” patients, given the declining number of commercially insured individuals. To offset the lower reimbursements attributed to caring for Medicare and Medicaid patients, health systems have historically relied on revenue from their commercially insured patients to subsidize operating losses from other patient populations.19 Therefore, cost of care for the commercially insured will continue to increase despite declining volumes. These trends are also seen within public programs. While Medicare enrollment increased, the number and share of Medicare beneficiaries using home health declined by almost 10% from 2017 to 2020. Despite declining utilization, payments per home health user steadily increased, offering another example of Medicare payments being driven by price rather than volume.20 Our national analysis of telehealth also revealed the disproportionate relationship between demand and price for services.21

As post-pandemic realities accelerate the growth in the number of individuals insured under government-funded programs, those that can effectively leverage psychographic and consumer loyalty data to both increase current share of care from existing commercial patients, and identify which individuals have the potential to split their share of commercial care across more brands will maintain a competitive advantage. The entry of well-known consumer brands into the healthcare space will make the competition for health systems even more difficult, not only in terms of scale of “consumer stickiness” but on price.

7. The Role of Government in Healthcare Is Increasing.

With nearly half of all Americans covered by Medicare or Medicaid, the U.S. government is and will continue to be the single largest payer (and regulator) of healthcare services. Share of health system revenue from government payers increased by an average of seven percentage points between 2012 and 2020 from 42.1% to 49%. While the percent of revenue attributed to government payments spans a large range and the long-term implications of the temporal growth in Medicaid during the pandemic are still developing, the upper limit is nearing 70% for many health systems.22 As we navigate an eventual end to the public health emergency, lawmakers are crafting policies to consider making permanent some or all of the temporary regulations implemented throughout the pandemic (e.g., insurance subsidies, telehealth expansion, funding increases). However, policy proposals have not always aligned with utilization trends, evidenced in some research related to telehealth and opioid prescribing.23,24,25

The health economy has in some ways changed dramatically in the past year, and in other ways remains the same. The health economy continues to grow faster than the overall economy, approaching 20% of GDP, and continues to be the largest expenditure in the federal budget. The public health emergency remains in effect as America adjusts to a prolonged presence of COVID-19. As the downstream impacts of the pandemic continue to unfold, the mission of The Compass is even more critical today in navigating us toward an exponentially better health economy.

Data tells a story. Sometimes that story is optimistic and sometimes pessimistic. In an industry that creates more data than any other, there are an endless number of stories to share. Thank you to every reader who has used The Compass as a guide over the last year - here's to many more.

As always, your feedback, questions and suggestions are greatly appreciated at sanjula.jain@trillianthealth.com.

From examining the data to artfully articulating the intricacies of each data story, publishing these weekly analyses would not be possible without the support of the Trilliant Health team. My sincerest gratitude to the entire Research team and other colleagues for their tremendous research, visualization, and peer-review contributions.

- Health Reform

- Cost of Care

- Healthcare Consumerism

- Healthcare Workforce

- Disease Burden

.png)

.png?width=171&height=239&name=2025%20Trends%20Report%20Nav%20(1).png)