Studies Archive

Surge in Subspecialty Fellowships Reveals Shifting Priorities Among Internal Medicine Residents

June 30, 2024Key Takeaways

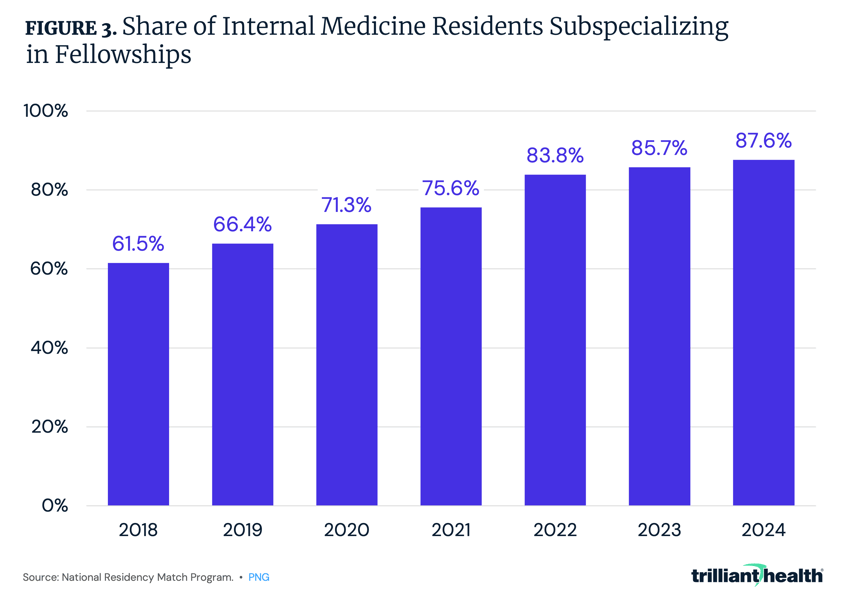

- Internal medicine residents are increasingly choosing to subspecialize as opposed to pursuing primary care or hospital medicine, with rates increasing from 61.5% in 2018 to 87.6% in 2024. This shift impacts the primary care workforce, particularly in rural areas.

- To prepare for the “next generation” of physicians, stakeholders must consider their mindset, priorities and expectations. As more young doctors weigh compensation against workload, how can primary care be better positioned as a specialty to align with their needs?

- Compass+ Exclusives: Average Physician Workloads, by Specialty & Analyzing Fill Rates of Internal Medicine Subspecialty Fellowships.

You are currently viewing the public version of The Compass.

To unlock additional analyses, upgrade your subscription to the Compass+ Portal.

Earlier this year, we analyzed the 2024 Residency "Match Day" results, highlighting that family medicine and internal medicine programs had the highest rates of unfilled residency positions at 6.5% and 2.5%, respectively, underscoring the accelerating shortage of primary care physicians (Figure 1).1 With residencies and many fellowships starting in June and July, we examined fellowship program matching results for subspecialties pursued after internal medicine residency.

Background

Despite the growth in primary care-centric residencies, the influx of new physicians has not offset workforce shortages, reflected in a -2.3% reduction from 2018 to 2022.2 By 2036, the U.S. may face a shortage of up to 86,000 physicians, with primary care facing a shortage of up to 40,400 physicians.3 The proliferation of new care models (e.g., retail) further constrain physician supply, amid a trend of declining primary demand with 2022 primary care volumes down 8.4% compared to 2019.4,5 Notably, only 4% of residents responding to a 2023 AMN Healthcare survey were interested in working in rural areas, where 66.7% of primary care Health Professional Shortage Areas are located, leaving these areas increasingly reliant on allied health providers.6,7

Internal medicine residency programs span three years, after which residents can choose specialty medicine fellowships (e.g., oncology, gastroenterology), or primary care or hospital medicine. Researchers have studied the timing, predictors and barriers internal medicine residents face when choosing career paths, given the numerous specialization and care setting options available.8,9,10,11 Surveys reflect an overall desire for more flexible schedules, less documentation and higher salaries.12 Notably, lifestyle, personal time and schedule flexibility were “very important” factors for 82%, 80% and 65% of AMN resident survey respondents, respectively.

The AMN survey reveals that residents increasingly prefer hospital employment over independent group practice models, with 68% reporting a preference for hospital employment in 2023, up from 32% in 2011. Whether someone is a hospital-employed internal medicine physician or a specialist (e.g., gastroenterologist), the pay, job satisfaction and contentedness with their chosen field is much higher among the internal subspecialties, with 61% and 66% of internal and family medicine physicians, respectively, relative to 92% of gastroenterologists, reporting a desire to remain in their specialty if given the choice.

Low relative pay, high student loan debt, declining Medicare reimbursement and large patient panels are often cited as the main deterrents of pursuing primary care.13,14,15 While specialist physicians work longer hours on average as compared to family medicine (48 hours) and internal medicine (51 hours), specialist pay is significantly higher (Figure 2 Compass+ Exclusive). Notably, physicians under age 35 are estimated to work 13% fewer hours than the previous generation.16

Given evolving physician preferences, persistent primary care shortages and increased investments in primary care training, how many internal medicine residents are choosing specialty medicine over primary care?

Compass+ Exclusive: Average Hours Worked Per Week, By Physician Specialty

Analytic Approach

We analyzed the Main Residency Match (2015-2024) and the Specialties Matching Service® Fellowship Match (2018-2024), comparing internal medicine residency matches to post-residency fellowship matches three years later.17,18 Fellowship Matches occur throughout the year, each requiring its own registration process. Thus, data are reported for the appointment year instead of the match year. Study limitations include non-internal medicine residents pursuing these fellowships, gaps between residency and fellowship and lack of data on residents choosing primary care vs hospital medicine.

Findings

The share of internal medicine residents pursuing specialty medicine has steadily increased from 61.5% in 2018 to 87.6% in 2024 (Figure 3). This trend suggests a growing preference among internal medicine residents to pursue further specialization through fellowship programs.

Compass+ Exclusive: Analyzing Fill Rates of Internal Medicine Subspecialty Fellowships

Conclusion

Our analysis highlights the growing trend of internal medicine residents subspecializing, with rates increasing from 61.5% in 2018 to 87.6% in 2024. This shift impacts the primary care workforce, particularly in rural areas. To address the declining interest in primary care and the uneven distribution of medical professionals, several questions arise: What policies and initiatives can reengage the workforce and build a stronger culture for physicians, especially in rural areas? What incentives will be most effective in encouraging more medical students to train in primary care specialties? Will provider organizations start investing in their own community-based trainee development programs to take matters into their own hands?

Despite reports of burnout and dissatisfaction being exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the medical school pipeline has not faltered, with a commensurate number of 2023-2024 applicants and matriculants and average MCAT scores relative to past years.21 Addressing physician dissatisfaction and workforce shortages requires reevaluating physician education and wellness. As more new internal medicine physicians grapple with the choice to subspecialize or pursue primary care amid a growing preference for hospital employment arrangements, primary care must be better positioned to align with their goals and work environment. To prepare for the “next generation” of physicians, stakeholders must consider their mindset, priorities and expectations. As more young doctors weigh compensation against workload, how can primary care be better positioned as a specialty to align with their needs?

Moreover, the widening gap of primary care physicians creates a concerning feedback loop: a shrinking primary care workforce may lead to greater dissatisfaction and distrust in the healthcare system, which discourages patients from seeking care. Allied health professionals are serving growing role in primary care delivery, but new strategies are needed to strengthen the primary care workforce, including community training programs and reducing regulatory and administrative burdens that deter people from becoming physicians, choosing primary care or practicing until retirement.

Thanks to Marina Kheyfets and Katie Patton for their research support.

- Primary Care

- Specialty Care

- Healthcare Workforce

.png)

.png?width=171&height=239&name=2025%20Trends%20Report%20Nav%20(1).png)