Counterpoint

Hal Andrews | March 6, 2024A Practical Approach to Health Equity

After four decades in the healthcare industry, I have become accustomed to the proliferation of concepts that are frequently discussed but rarely implemented at scale: the Triple Aim, value-based care, social determinants of health, etc. “Health equity” seems to be the concept du jour, and I have started to ask people who say those words to tell me what they mean. The most common response is a blank stare, and then mumbling.

In my experience, health equity can be measured at the intersection of income and access to healthcare services. As a general principle, high poverty and lack of access to care are highly correlated, whether in Clarksdale, Mississippi or Mamou, Louisiana or Livingston, Alabama or Berwick, Pennsylvania or Etna, California.

Maybe it is easy for me to define health equity because I have been to all those places, and dozens more. I don’t need a policy analyst or benefits consultant to tell me about health equity, or the lack thereof, because I have seen it.

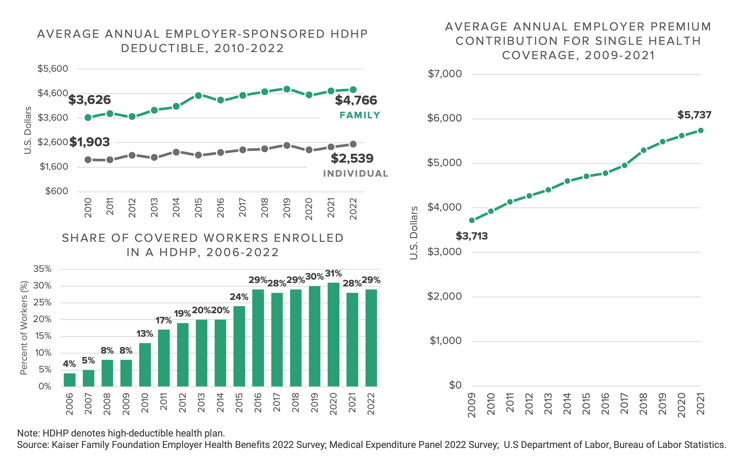

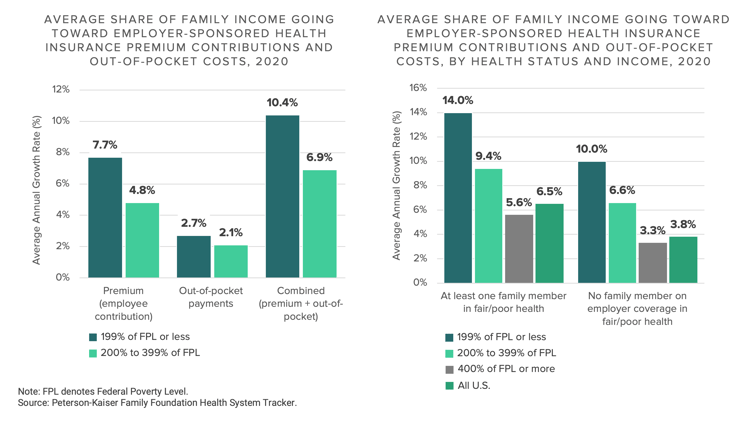

What is true in America today about the lack of access to healthcare services in poor areas has been true about healthcare in America since Benjamin Franklin founded Pennsylvania Hospital in 1751.1 What has changed is that the introduction of high-deductible health plans in 2003 has resulted in an increasing number of people with physical and contractual access to care who lack the financial wherewithal to use it.

In the last 35 years, I have met hundreds of people who lacked “health equity,” but none has ever talked about “health equity.” Instead, they talk about the year that the hospital closed or the family practice physician who closed his practice upon retiring because he could not recruit another physician to town or the fact that there is only one ambulance in the county or how they cannot afford their medicine.

Instead of merely talking about health equity in the halls of Congress and Washington think tanks and research journals, I believe that the Federal government could revive the program that did more to provide healthcare access than anything in U.S. history: the Hill-Burton Act.

In 1946, President Truman signed the Hill-Burton Act, which provided grants and loans to hospitals, nursing homes and other healthcare facilities, subject to an agreement to treat patients without regard to their ability to pay.2 Between 1946 and 1975, it is estimated that almost 10,000 medical facilities and 33% of all hospitals were financed in part through the Hill-Burton Act.3

Anyone who has ever driven the South like Paul Theroux, or even driven 100 miles from a major metropolitan CBSA, has seen a Hill-Burton facility, many of which are low-slung, L-shaped buildings like this4:

Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the counties and towns that needed assistance to build modern healthcare facilities in the post-WWII era are those where a lack of health equity is most obvious today. Some of those Hill-Burton hospitals are now designated as critical-access hospitals; some have been converted into nursing homes; some have closed. None of the original Hill-Burton facilities that remain open are designed or equipped to provide anything more than the most basic hospital services today.

Instead of talking about health equity, Congress could do something about it by enacting the 2024 Hill-Burton Act. Instead of providing grants and loans to develop new hospitals, the 2024 Hill-Burton Act could provide access to capital to develop modern ambulatory facilities equipped to provide appropriate levels of interventional medicine and digital health.

Like the original Hill-Burton Act – and EMTALA – the Federal government could require that these modern facilities treat patients without regard to their ability to pay, while using something akin to disproportionate share payments to underwrite care delivered to uninsured patients. These modern facilities could replace critical access hospitals and federally qualified health centers, providing new investment and improved healthcare access in poorer communities. These modern facilities might resemble those that the Veterans Administration has recently opened5:

For more than 20 years, I have been attending gatherings of self-referential and self-reverential healthcare executives discussing the innovation and transformation that the U.S. healthcare system needs in the conference rooms of five-star hotels. I can count on one hand those Teddy Roosevelt described this way:

“the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”6

Only one of those executives ever did something that proponents of health equity would applaud, founding a company to create access to state-of-the-art healthcare services for people who lacked it, most of whom lived in poor, rural communities. Working for that executive was one of the most transformative experiences in my career, even though the company ultimately failed because CMS and commercial payers were unwilling to adopt an “alternative payment model” that would make those facilities financially viable.

The Apostle James reminds us that faith without works is dead, and so is talking about health equity without doing something tangible to provide poor people with access to healthcare services that they lack. With respect to health equity, are you in the arena?

- Featured