Trilliant Health

Use Cases

Develop Service Line Strategies

Analyze the Competitive Landscape

Anticipate Future Patient Needs

Identify Sites To Capture Demand

Drive Loyalty Across the Patient Journey

Leverage Price Transparency Insights

Retain Patients in Your Network

Match Provider Supply to Demand

Industries

Acquire Commercial Patients

Capture Outpatient Demand

Target High-Value HCPs

Strengthen Provider Networks

Our Data

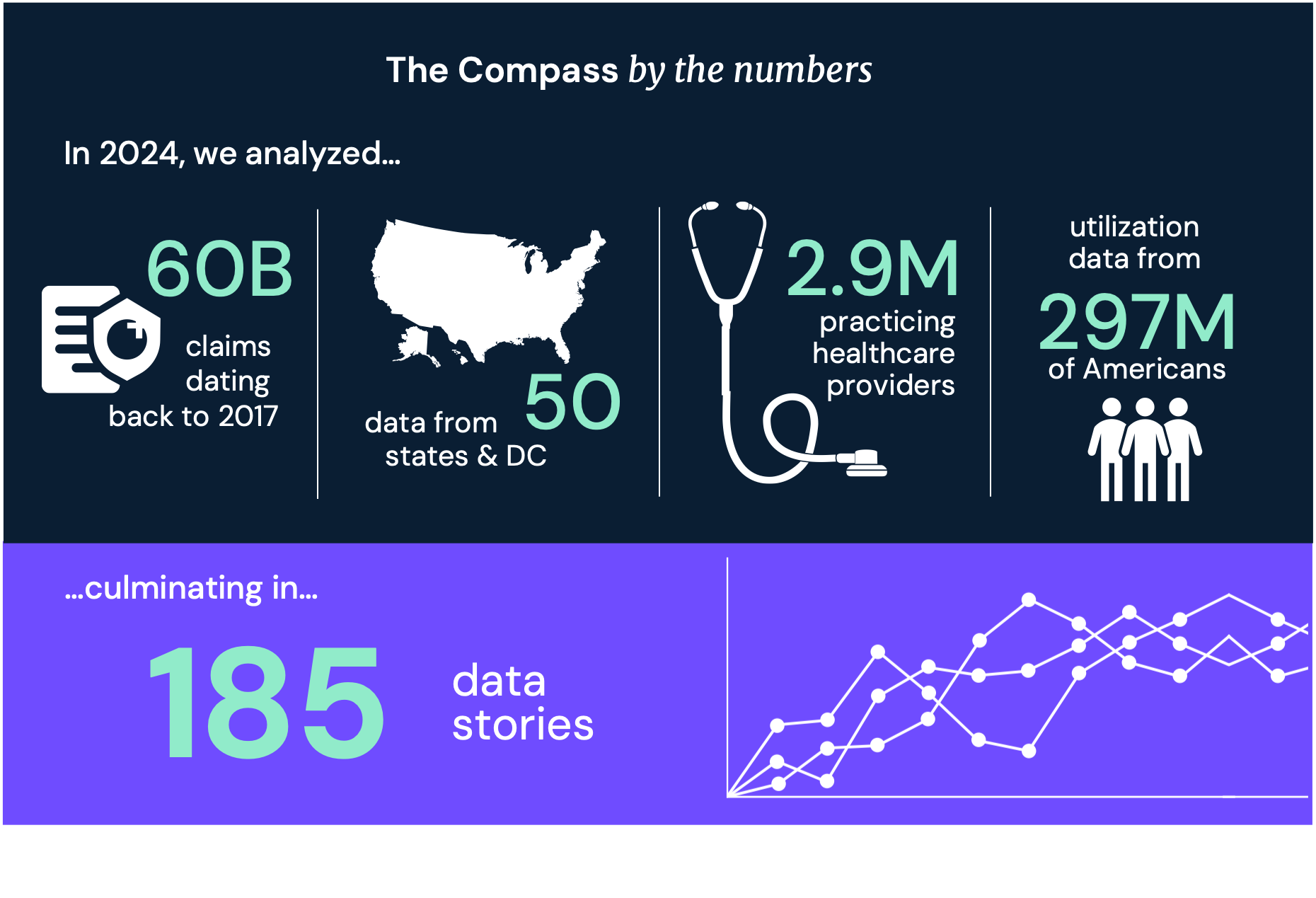

We collect and organize the industry’s most comprehensive healthcare datasets.

Data Pipelines

See demand, supply and yield across the U.S. health economy

Validated Data for 2.9M Practitioners

Episodes of Care for 300M Patients

Negotiated Rates for Any Service at Any Location

Ways to Access

Resources

Flexible solutions to fit your specific needs and workflow

Free resources to help health economy stakeholders use our products and data

Answer Key Questions in Seconds

AI Chatbot for Hospital Prices

Custom Enterprise-Level Analyses

Data-Driven Benchmarking Tool

Inform Data-Driven Strategies

Health Economy Survival Strategies

Product Guides and Feature Releases

Strategic guidance and commentary from our CEO, Hal Andrews

.png)

Analysis of trends shaping the health economy

Original research on trends shaping the health economy

Use Cases

Develop Service Line Strategies

Analyze the Competitive Landscape

Anticipate Future Patient Needs

Identify Sites To Capture Demand

Drive Loyalty Across the Patient Journey

Leverage Price Transparency Insights

Retain Patients in Your Network

Match Provider Supply to Demand

Industries

Acquire Commercial Patients

Capture Outpatient Demand

Target High-Value HCPs

Strengthen Provider Networks

Our Data

We collect and organize the industry’s most comprehensive healthcare datasets.

Data Pipelines

See demand, supply and yield across the U.S. health economy

Validated Data for 2.9M Practitioners

Episodes of Care for 300M Patients

Negotiated Rates for Any Service at Any Location

Ways to Access

Flexible solutions to fit your specific needs and workflow

Answer Key Questions in Seconds

Custom Enterprise-Level Analyses

Inform Data-Driven Strategies

Resources

Free resources to help health economy stakeholders use our products and data

AI Chatbot for Hospital Prices

Data-Driven Benchmarking Tool

Health Economy Survival Strategies

Product Guides and Feature Releases

Strategic guidance and commentary from our CEO, Hal Andrews

.png?width=171&height=239&name=2025%20Trends%20Report%20Nav%20(1).png)

Analysis of trends shaping the health economy

Original research on trends shaping the health economy