Counterpoint

Hal Andrews | January 27, 2021Winning a Losing Game, Part III: Why Health Systems Don’t Know Their Actual Market Share

The hospital business is a negative-sum game.

In a negative-sum game, “the only way for a party to maintain its position is to take something from another party, and even if everyone takes his or her share of the ‘losses,’ everyone still loses in comparison to what they currently have or really need. This type of situation often sparks serious competition.”[1]

In any competitive market, especially a negative-sum market, market share is the most important metric to measure wins and losses. As a result, analyzing market share correctly is fundamental to survival.

Most healthcare systems fundamentally misunderstand market share, in large part due to their historic focus on inpatient care. Similarly, most healthcare systems misunderstand or underestimate the market forces that determine market share.

Why? Because many health systems, including many of the most well-regarded health systems in the country, develop and execute operational and financial strategies based on self-reported data about inpatient admissions, aka “state data.”

The Siren Call of State Data

What is state data, and how is it collected? According to the National Association of Health Data Organizations (NAHDO),

“there are three models of governance for state health data agencies, which may impact release of data and allowable uses:

-

- A state agency with a legislative mandate collecting the data.

- A delegated authority, such as hospital association or private entity, collecting data under a state mandate.

- A private agency, usually a hospital association, collecting the data voluntarily from its members and community hospitals.”[2]

NAHDO summarizes the following characteristics of state data:

-

- They are population based, representing a known population that is defined by residence within geographic or political boundaries.

- Are increasingly being used for community assessment, providing information about preventable, avoidable hospitalizations, including ambulatory care sensitive conditions.

- Data contain a large volume of observations on all patients hospitalized in short-term-care facilities in a state (federal hospitals and specialty hospitals are often excluded from state data collection requirements).

- More states are adding data elements important for public health and research to their discharge data in response to national standards and user needs for example Ecodes and POA (present on admission).

- Data are based on national standards established by the National Uniform Billing Committee and thus, are relatively comparable across states.

- Data quality is usually higher than other injury data as data are collected by licensed/certified professional medical record coders and serve as the basis for payment.

NAHDO omits several salient facts. Not only is the data self-reported, but in many cases, it is entrusted to the employees of a small lobbying association, aka the state hospital association. Trusting state data requires believing that every hospital in the state reported the data correctly in accordance with a consistent methodology while simultaneously believing that lobbying organizations are extremely proficient at data ingestion, normalization, de-duplication and analysis. Data use agreements prohibit publishing a laundry list of obvious mistakes, but it is clear to us that de-duplication is not a strong suit for many organizations. And, “relatively comparable” is most definitely a relative term.

The reality is that health systems have survived in spite of their reliance on state data. If Progressive Insurance’s Dr. Rick held a seminar for health system executives, he would undoubtedly make them repeat this mantra: “State data is useless.”

How can something so useless be so esteemed? Why do health system executives blindly trust state data? In what other industry are strategic plans developed and millions and billions of dollars invested based on a subset of data gathered by industry lobbyists?

Because state data is completely self-referential.

Health system executives have complete confidence in state data because they evaluate all of the reporting agency’s work against what it reports about their hospital. In a stunning combination of circular logic and confirmation bias, health systems validate their belief in what is reported by the reporting agency by comparing it to what the health system reported to the reporting agency, without regard to whether what they reported was accurate. Voila!

Assuming, for argument’s sake, that all state data is accurate, it is still completely useless as a predictive tool. What’s past is not prologue in healthcare, as 2020 manifested in stunning fashion. Perhaps health systems will have an epiphany in 2022 and 2023 when the 2020 state data is released.

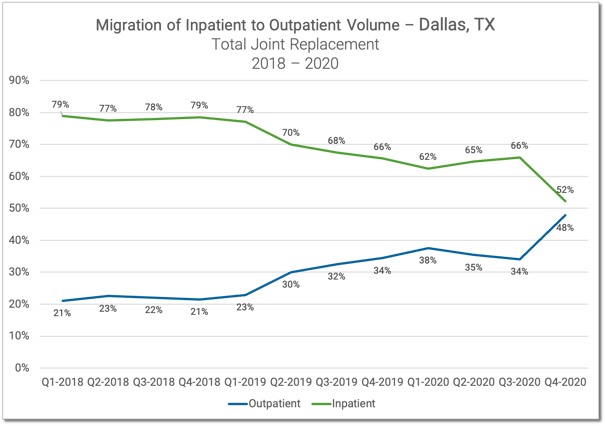

Even if state data were both accurate and predictive, it is fatally flawed by its focus on inpatient care, which represents less than half of the volume of, and charges for, the care delivered in the U.S. healthcare market.[3] This trend will accelerate with elimination of the “inpatient only” list by 2024.[4] Moreover, CMS’s National Health Expenditure (NHE) projections indicate that from 2024-2028 increases in hospital spending will be driven by Medicaid, while physician and clinic spending will be driven by Medicare and private health insurance.[5] The NHE projections were developed before the pandemic shifted consumer preference towards outpatient settings out of fear of contracting SARS-CoV-2 from a hospital visit.

If state data is neither accurate nor predictive nor representative, what should health systems do to win a negative-sum game?

How Consumer-Focused Enterprises Think: “Total Addressable Market”, not “Primary Service Area”

I am embarrassed to admit that, in a previous role, I purchased a dozen or so “market share reports” from HCIA-Sachs/Solucient before I figured out that the reports always seemed to define the Primary Service Area according to the Pareto principle. Today, my only comfort is to imagine that I could fill McCormick Place with health system executives like me.

Twenty years later, it is obvious to me that the proportion of a health system’s inpatient admissions as compared to other hospitals in the area is increasingly irrelevant, because the available market for profitable inpatient admissions is declining, as this analysis of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex makes clear:

In a negative-sum game, particularly in an industry that, according to projections by the Commonwealth Fund, lost 10% of its best customers in a matter of months, understanding market share is essential.[6] Why? Because only with a comprehensive understanding of the competitive dynamics in local markets can healthcare systems effectively allocate scarce resources across their enterprise. Only with a comprehensive understanding of the individuals in each market can healthcare systems compete effectively for a shrinking number of commercially insured patients.

To develop a better understanding of the consumption of all healthcare services in your market requires the right mindset as well as the right information.

How do consumer-focused enterprises think?

First, unlike health systems, consumer-focused enterprises do everything they can to understand consumers in their market, both customers and prospects, how much business the competition has, how and where to reach the customers of the competition, whether those customers are valuable, and how to take those customers away from the competition.

Secondly, unlike health systems, consumer-focused enterprises assume that they do not have all of the business of their customers. Notably, those in negative sum industries understand that the key measure of success is not whether they do more but whether the competition does less.

Third, consumer-focused enterprises are keenly aware of their product mix, which is analogous to a hospital’s service lines. Everyone knows that Whole Foods does not sell gasoline, and 7-Eleven does not sell New Zealand Lamb Shank. In contrast, hospitals strive to be all things to all potential patients, branding every service line as a “Center of Excellence”, which is diametrically opposed to the “focused factory” strategy proposed by Professor Regina Herzlinger in her 1996 book “Market Driven Health Care.”

With a changed mindset comes a completely different set of questions:

-

- What is the total available market of healthcare services, both inpatient and outpatient, that your system does or could provide within a defined geographic market?

- What are the general and specific growth trends in that market? Are new competitors entering that market?

- Who are all of the competitors in that market who provide any services similar to those of your health system?

- What is your market share percentage and trend by service line for the entire market?

- Optum Care, aka UnitedHealth Group, has more than 53,000 providers and more than 1,450 clinics serving more than 19M (commercially insured) lives.[7] How many providers and clinics and patients does Optum have in your market?

- Having answered all of these questions, which service lines can/should you grow? Which service lines should you abandon?

There is no way to win a losing game without competing, but there are a number of ways to compete seriously: winning key battles, cutting losses early, losing less frequently, and losing by a smaller margin than the competition. However, winning more or losing less than the competition is virtually impossible without accurate and actionable information.

So, ask yourself: Do I know who my patients are? Do I understand their preferences, buying power, or future needs? Then compare what you know about your patients to your service lines, access points, and patient experience initiatives. How well is your system meeting and anticipating the needs of the consumers in your market? The answer to that is how to gain market share.

PART IV: Thinking About Customers – and Pricing – Like Amazon

PART II: Lessons from Nick Saban on Thinking Like a Champion

PART I: Winning a Losing Game, Healthcare Edition

[1] https://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/sum

[2] https://www.nahdo.org/data_resources

[3] https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/downloads/highlights.pdf

[4] https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/cy-2021-medicare-hospital-outpatient-prospective-payment-system-and-ambulatory-surgical-center-0

[5] https://www.cms.gov/files/document/nhe-projections-2019-2028-forecast-summary.pdf

[6] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/oct/how-many-lost-jobs-employer-coverage-pandemic

[7] https://www.optumcare.com/about/about.html

- Winning a Losing Game

.png)

.png?width=171&height=239&name=2025%20Trends%20Report%20Nav%20(1).png)