Counterpoint

Hal Andrews | May 3, 2023Employers Care About Value for Money, Not Value-Based Care

In last month’s Counterpoint, I wrote this:

To any disinterested observer, it is obvious that value-based care is insufficient to cure the financial ills of the U.S. healthcare system.

Only value-based competition can do that.

Why? Well, first, as even the most avid policy wonk will admit, there is no tangible evidence that value-based care is consistently effective or scalable after 15 years of CMS pilot programs. Second, and more importantly, value-based care isn’t designed to deliver value to the ultimate payer.

The Problem With Value-Based Care Platforms in the U.S.

There are examples of highly profitable value-based care platforms in the U.S., or at least a handful of people who have developed enduring value-based care franchises. Herb Fritch (NAMM, HealthSpring), George Rapier III, M.D. (WellMed), Norm Chenven, M.D. (Austin Regional Clinic), Jose “Pepe” Armas, M.D. (MCCI), Benjamin Leon, Jr. (Leon Medical Centers), Jen-Ling James Chen, M.D. (ChenMed) and Robert Margolis, M.D. (Healthcare Partners) all mastered the art of taking capitated rates, providing broad primary care services to their members and tightly managing referrals of those members to specialists. Perhaps not coincidentally, these models have worked brilliantly for decades but only in select markets, primarily Miami, Austin, San Antonio and Southern California. However, the efficiencies created by these primary care models accrue to the owners of the platform, not the employer or Federal government.

In 2004, Michael Porter and Elizabeth Teisberg wrote this about “positive-sum competition”:

For that process to begin, however, the locus of competition has to shift from “Who pays?” to “Who provides the best value?” Getting there will require changes in the strategies of providers and payers and in the behaviors of employers purchasing health plans…

Under positive-sum competition, providers would not attempt to match competitors’ every move. Instead, they would develop clear strategies around unique expertise and tailored facilities in those areas where they can become distinctive…

Prices would be posted and readily available. Providers would charge the same price to any patient for addressing a given medical condition, regardless of the patient’s group affiliation. Providers could and would set different prices from their competitors, but that pricing would not vary simply because one patient was insured by Aetna, another covered by Blue Cross, and another self-insured. Payers could negotiate, but price changes would have to benefit all patients, not just their own. The cost of treating a medical condition has nothing to do with who the patient’s employer or insurance company is…

Positive-sum competition would induce payers to compete to create value, not just to minimize cost.1

(Emphasis added)

Health plans have little incentive to make value-based care programs work, despite the best intentions of the naïve or the knave who drafted the Affordable Care Act’s provisions with respect to the Public Health Service Act (the “PHS Act”):

Section 2718 of the PHS Act includes two provisions designed to achieve the objective in the section title: "Bringing down the cost of health care coverage.'' The first is the establishment of greater transparency and accountability around the expenditures made by health insurance issuers. The law requires that issuers publicly report on major categories of spending of policyholder premium dollars, such as clinical services provided to enrollees and activities that will improve health care quality. The second is the establishment of MLR standards for issuers, which are intended to help ensure policyholders receive value for their premium dollars. Issuers will provide rebates to enrollees when their spending for the benefit of policyholders on reimbursement for clinical services and quality improving activities, in relation to the premiums charged, is less than the MLR standards established pursuant to the statute. The rebate provisions of section 2718 are designed not just to provide value to policyholders, but also to create incentives for issuers to become more efficient in their operations.2

(Emphasis added)

Of course, the road to Hell is paved with good intentions as well, and the Affordable Care Act’s minimum medical loss ratio (“MLR”) requirements codified health plans’ maximum profit margin on fully funded health plans, perversely incentivizing them to raise premiums continuously, the health insurance industry’s version of “cost-plus” reimbursement. Since the MLR requirements do not apply to self-funded plans that cover 65% of the commercially insured population, health plans are not required, and have no incentive, to create value for their administrative services lines of business.3 So, in conclusion, the ACA does nothing to incentivize value for 65% of the commercially insured population and codifies disincentives to value for the other 35%.

“Value-Based Care” ≠ “Value for Money”

In any event, employers don’t want value-based care and don’t pretend to know what it means, in contrast to the thousands of consultants, policy wonks and entrepreneurs prattling on about it for the past two decades. The phrase “value-based care” is almost Orwellian, meaning virtually anything and therefore almost nothing.

Applying Porter and Teisberg’s framework above, value-based care does not create value for the ultimate payer, whether the employer or the Federal government, but simply allows that ultimate payer to cap its financial exposure. Why? Value-based care participants focus on minimizing cost after negotiating the revenue pool from the ultimate payer to maximize marginal income on their share of the available funds, aka “subcapitation.”

Value-based care never delivers maximal cost-effectiveness for the ultimate payer, which the British call “value for money,” a concept enshrined in The NHS Constitution for England:

6. The NHS is committed to providing best value for taxpayers’ money

It is committed to providing the most effective, fair and sustainable use of finite resources. Public funds for healthcare will be devoted solely to the benefit of the people that the NHS serves.4

The British are serious enough about “value for money” to attempt to define it, as well as acknowledge the challenges in measuring it:

The traditional accounting framework for discussing value for money is…[f]inancial inputs (in the form of costs) are converted into physical inputs (such as labour and capital). The success of this conversion is often referred to as the ‘economy’ with which inputs are purchased. Physical inputs are in turn converted into physical outputs (such as an episode of hospital care). The relationship between physical inputs and outputs is often referred to as ‘efficiency’. Depending on the quality of care, the physical outputs then create eventual outcomes, for example, increases to the quality and length of life. The success of this conversion is referred to as ‘effectiveness’.

It is conventional to consider various value for money measures under these headings. For example, the traditional measure of ‘length of stay’ for a hospital episode is an efficiency measure as it indicates the level of physical inputs (bed days) required to produce a physical output (an ‘episode’). In contrast, the post-operative mortality rate is a measure of the quality of that output and therefore a signal of effectiveness. The holy grail of value for money is therefore cost-effectiveness: the ratio of outcomes to inputs. For example, the ‘cost per quality adjusted life year’ used by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) to assess new technologies is a cost-effectiveness ratio, and the recent efforts to develop a single number measure of NHS productivity represent an attempt to move from the piecemeal assessment of indicators of economy, efficiency and effectiveness towards a more comprehensive measure of cost-effectiveness…

Recent work in estimating system productivity has developed innovative approaches, such as seeking to incorporate measures of quality alongside measures of inputs and activity. In the context of Figure 1, this implies a desire to incorporate measures of effectiveness into the value for money analysis. However, because of the difficulties associated with defining and measuring quality, little consensus has yet to emerge as to the ‘correct’ or most appropriate approach.5

The British are also refreshingly honest about the challenges of defining a “quality outcome”:

Any assessment of a health service ought to examine indicators of the value of the ‘output’ it creates. Traditionally, two classes of outcome are considered important in healthcare: clinical outcomes expressed in terms of the health gains created by the system, and the quality of the patient experience, independent of health outcomes, expressed in concepts such as ease of access to care and responsiveness.

Some health outcomes indicators – such as life expectancy rates, infant mortality rates and cancer mortality rates – are available. However, improvements in these are a function of many factors over which the NHS often has little influence. The relative scarcity of readily accessible outcome data specific to the NHS forces any analysis to rely heavily on process indicators, on the assumption that they provide a reasonable proxy for health outcomes.6

(Emphasis added)

Elements of Value in Healthcare Services

The most important elements of value in healthcare services are cost, quality, safety and convenience, but any knowledgeable observer of the U.S. healthcare system knows that the British are spot on about the availability of health outcomes metrics. What is less frequently discussed is the fact that the importance of quality as an element of value is highly variable depending on the type of care. Quality, which is critically important in neurosurgery, is almost irrelevant in an ankle X-ray as long as the patient doesn’t move.

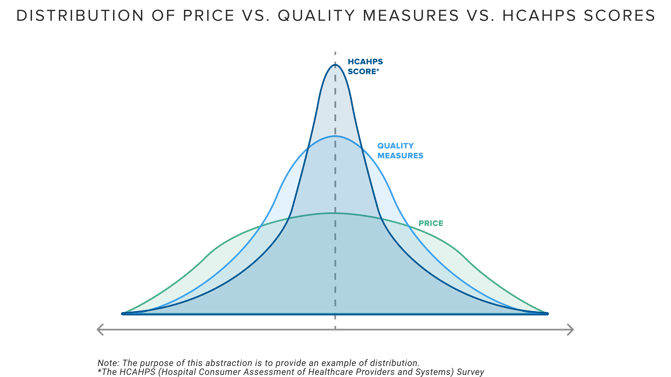

One outcome of CMS’s quality reporting initiatives is that the relative difference between providers on common quality measures has narrowed, just as it has for patient satisfaction, in stark contrast to the standard deviation for negotiated price for healthcare services.

As a result, under any definition of quality, increasing “value for money” in today’s health economy depends primarily on the cost of the services. Health plan price transparency now reveals the variation in cost across markets and service lines for those who can link the identity of a provider with the services that a provider renders, the locations at which that provider renders those services, and the reimbursement that the provider receives for those services. As a result, health plan price transparency should inaugurate an era of value-based competition borne of employers (and CMS?) focusing on value for money.

Notably, several concepts promoted by stakeholders and consultants in the health economy are antithetical to creating value for money. The value of the narrow provider networks “created” by health plans is generally limited to the network discount applicable to that narrow network, which incentivizes providers to raise prices simply to maintain current revenue levels, which incentivizes payers to demand a higher discount, a continuous game of Three-card Monte in which the employer is the mark.

Likewise, many “centers of excellence” are not, and obviously no single hospital or health system is the “best” at every single service line. It is self-evident that a “narrow network” designed around a single health system does not create value for money but instead inevitably sacrifices some aspect of quality at the altar of price. Similarly, any narrow network designed around inscrutable “quality outcomes” is incapable of creating the most value for money.

Producing value for money for employers requires value-based competition by providers across every service line, meaning that open networks and any willing provider statutes are essential. Employers should design benefits at the service-line level in every market, creating incentives for employees to use the best value provider, whoever and wherever they are. Instead of paying “quality bonuses” under the pretense that “outcomes” other than mortality are tangible or that providers can control consumer behavior like ordering a McDonald's Big Mac®️ or a Starbucks Frappucino®️, consumers should have the freedom to choose whatever provider they want together with the financial accountability for making poor choices.

The healthcare cost curve has been “up and to the right” for as long as any of us been alive, and every American needs that to change. Quality initiatives and the “triple aim” have failed to bend the cost curve meaningfully, if at all, because quality metrics are highly intangible. Cost is tangible, and health plan price transparency brings exactly that – transparency about what every provider was paid for the services the providers rendered at the location at which they rendered it.

In full disclosure, I currently have four direct or indirect investments in value-based care platforms, which demonstrates my belief in the underlying business model of those companies. At the same time, I now have the unique vantage point to see what 2.7M healthcare providers are being paid, which informs my belief about what is about to unfold in the health economy.

As employers begin to discover how little value for money they are receiving – and specifically who the lowest value providers are – they may begin to think of “value-based care” as the British do: a reimbursement “scheme.” Employer CFOs will soon realize that health insurance brokers are mercenaries, not fiduciaries, even as those CFOs become increasingly aware of their fiduciary duty of care in the context of how employer healthcare costs impact net income.

The truth comes out “a little at a time,” in the words of Miranda Lambert, but it does always come out. Can you handle the truth?

.png)

.png?width=171&height=239&name=2025%20Trends%20Report%20Nav%20(1).png)