Counterpoint

Hal Andrews | June 7, 2023Can You Defend Your Rate?

In last month’s Counterpoint, I described the difference between “value-based care,” long the siren song of consultants and policymakers, and “value for money,” which is what employers – and the Federal government – actually want and need.

CMS’s Transparency in Coverage initiative is primarily focused on consumers, but as often happens in life, the unintended consequences are more impactful. Health plan price transparency reveals the most important, if unsurprising, fact since the creation of Medicare:

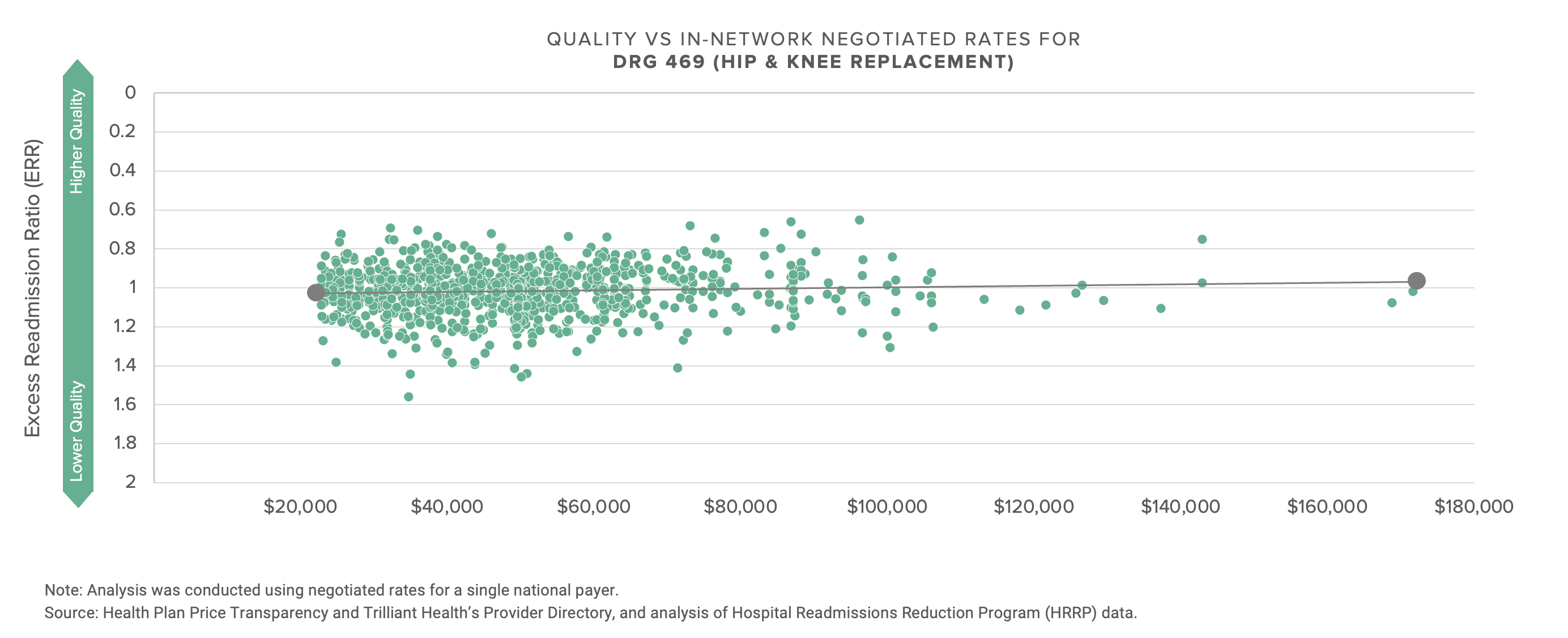

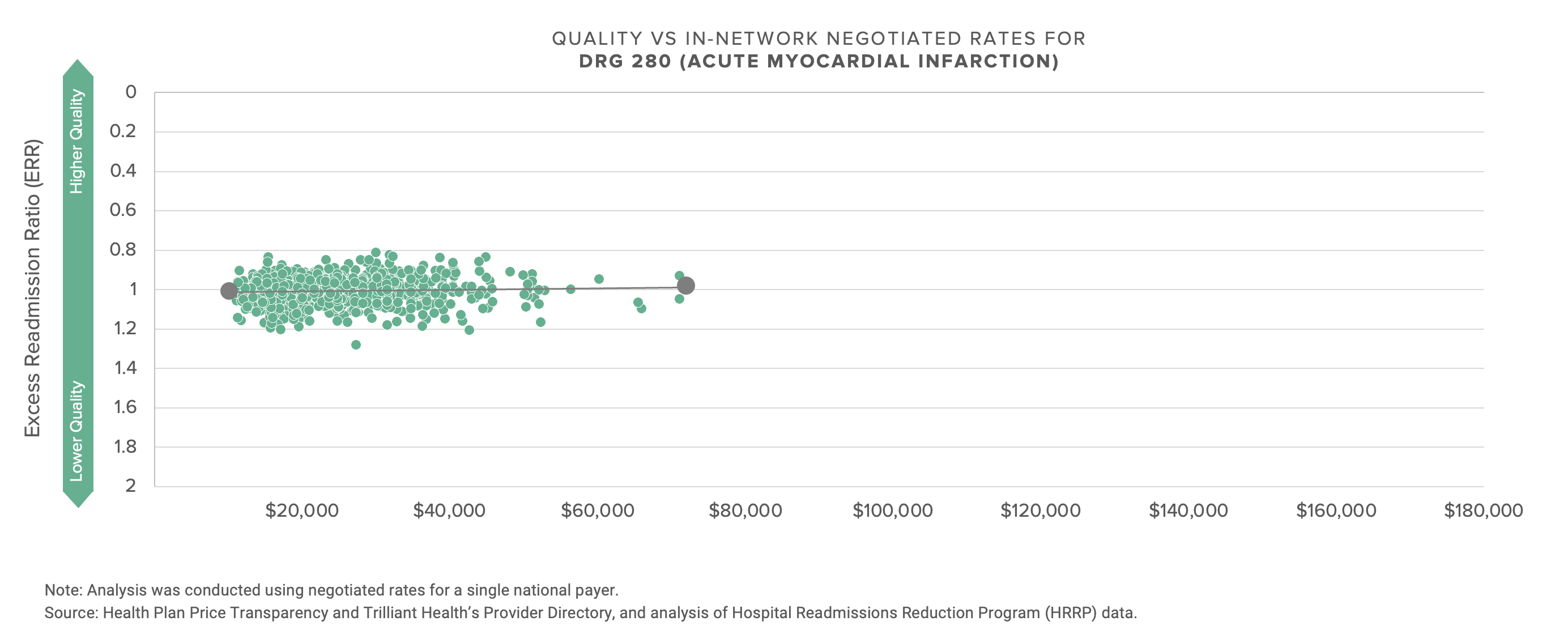

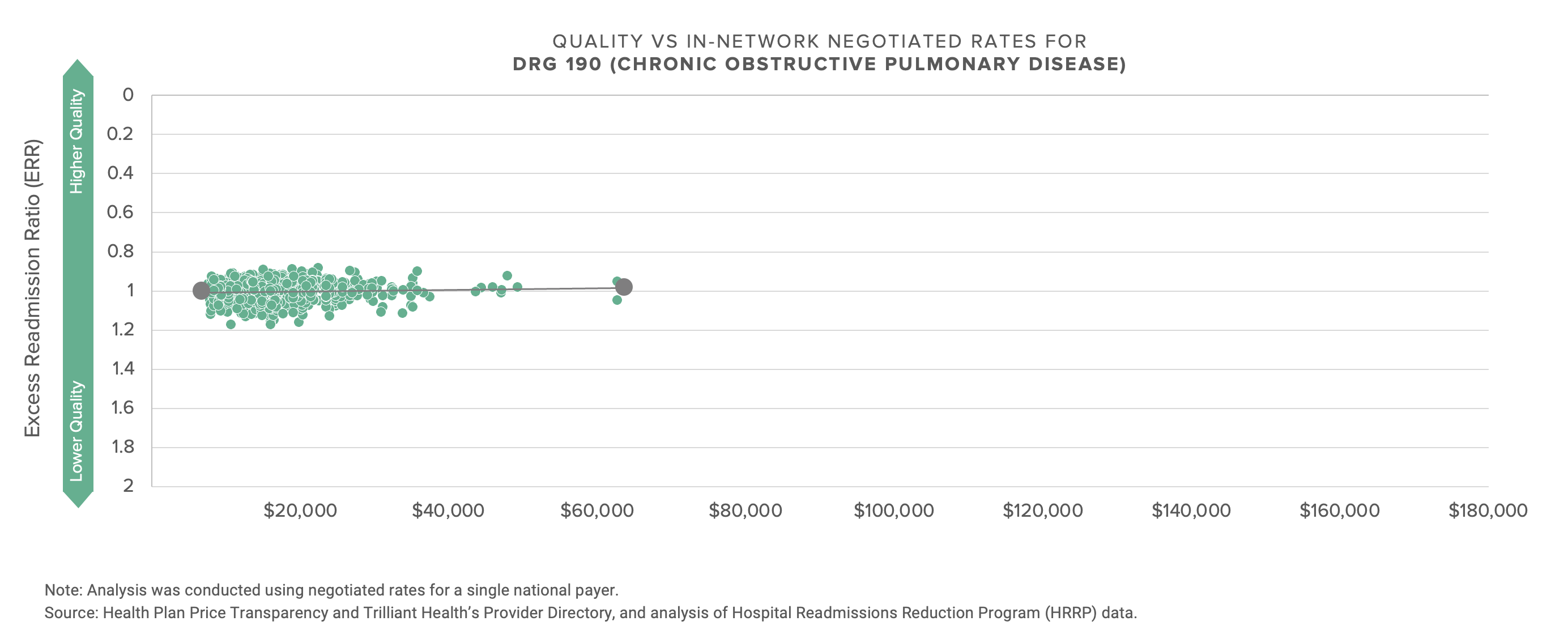

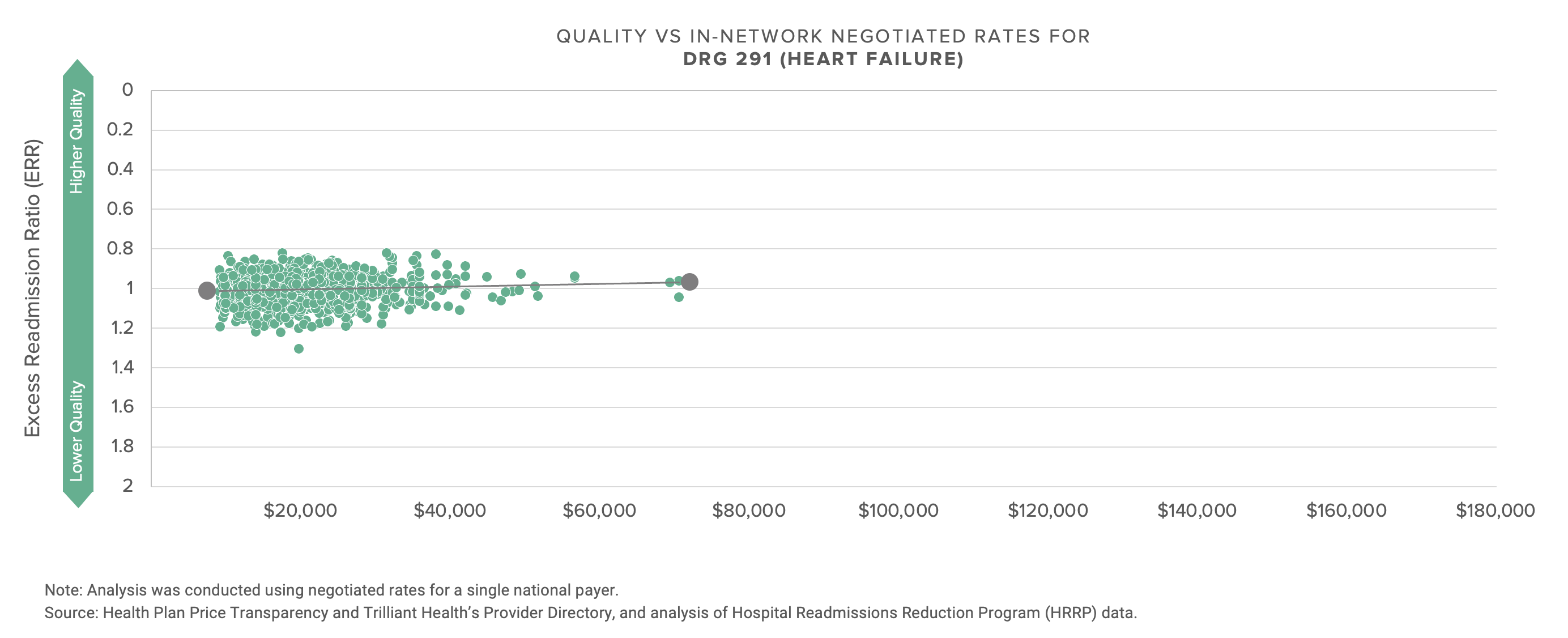

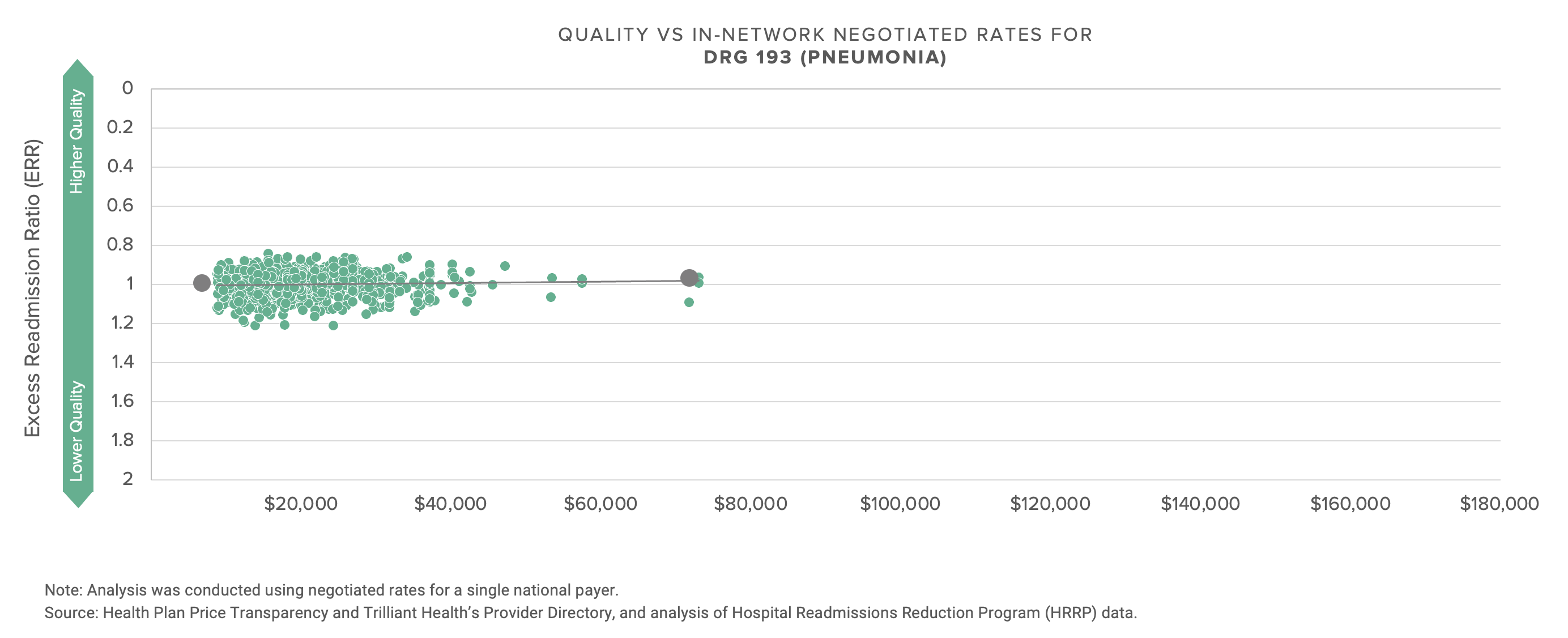

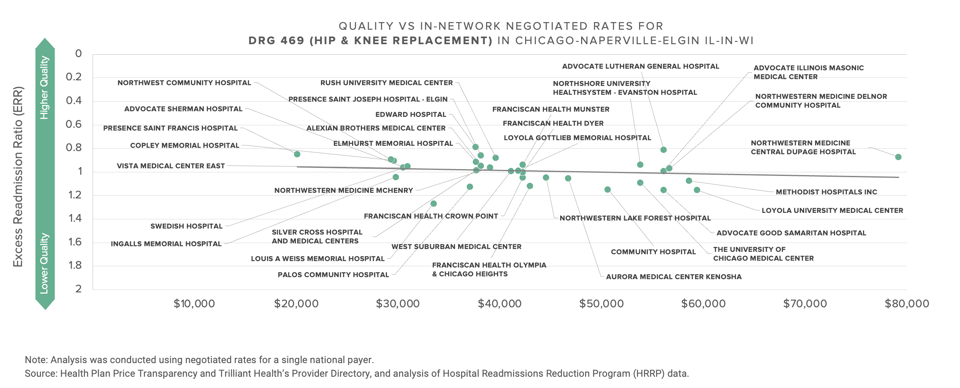

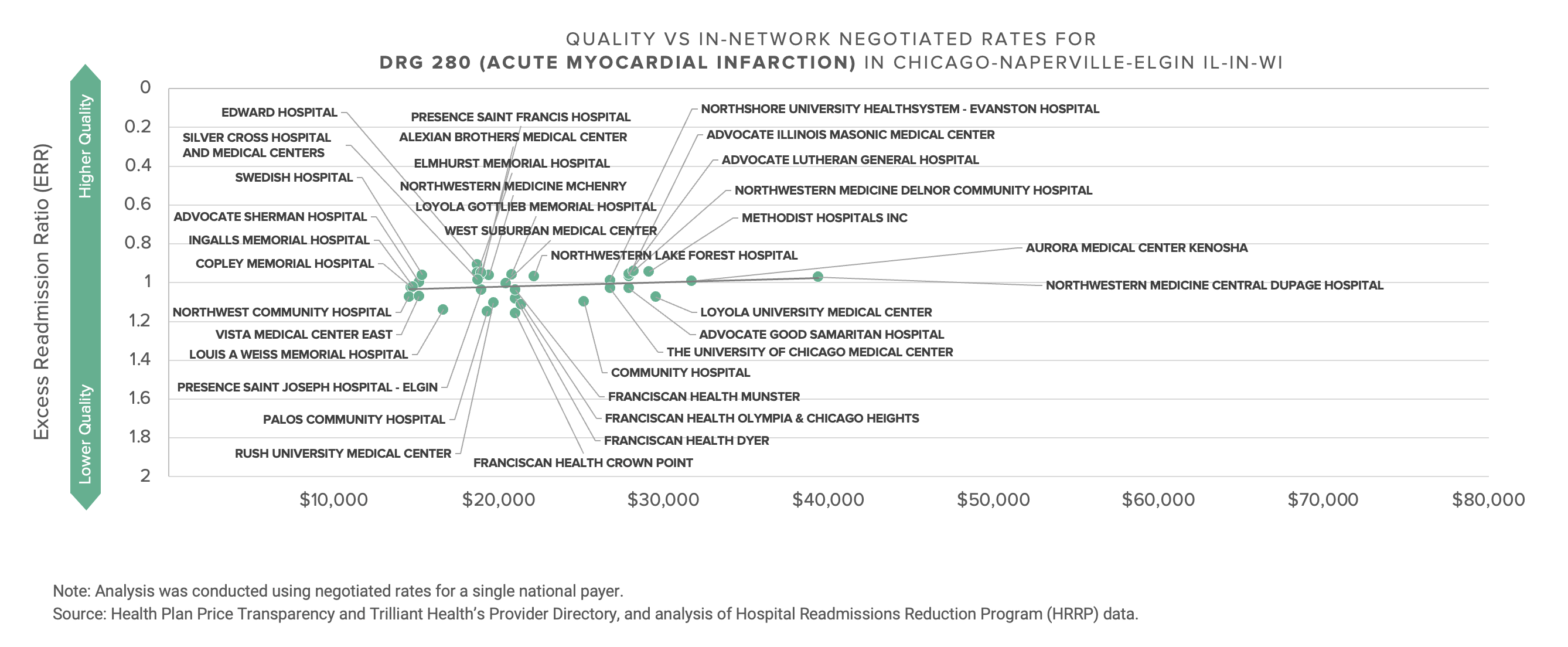

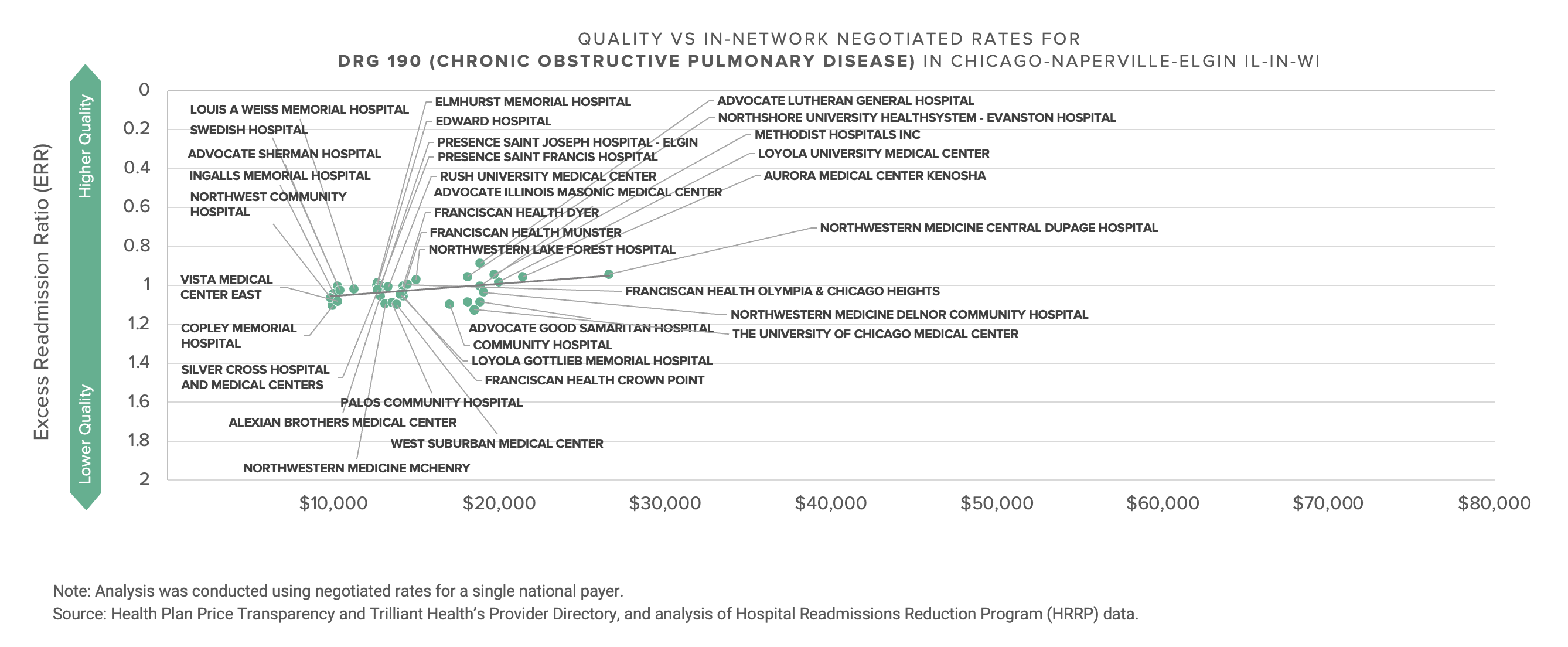

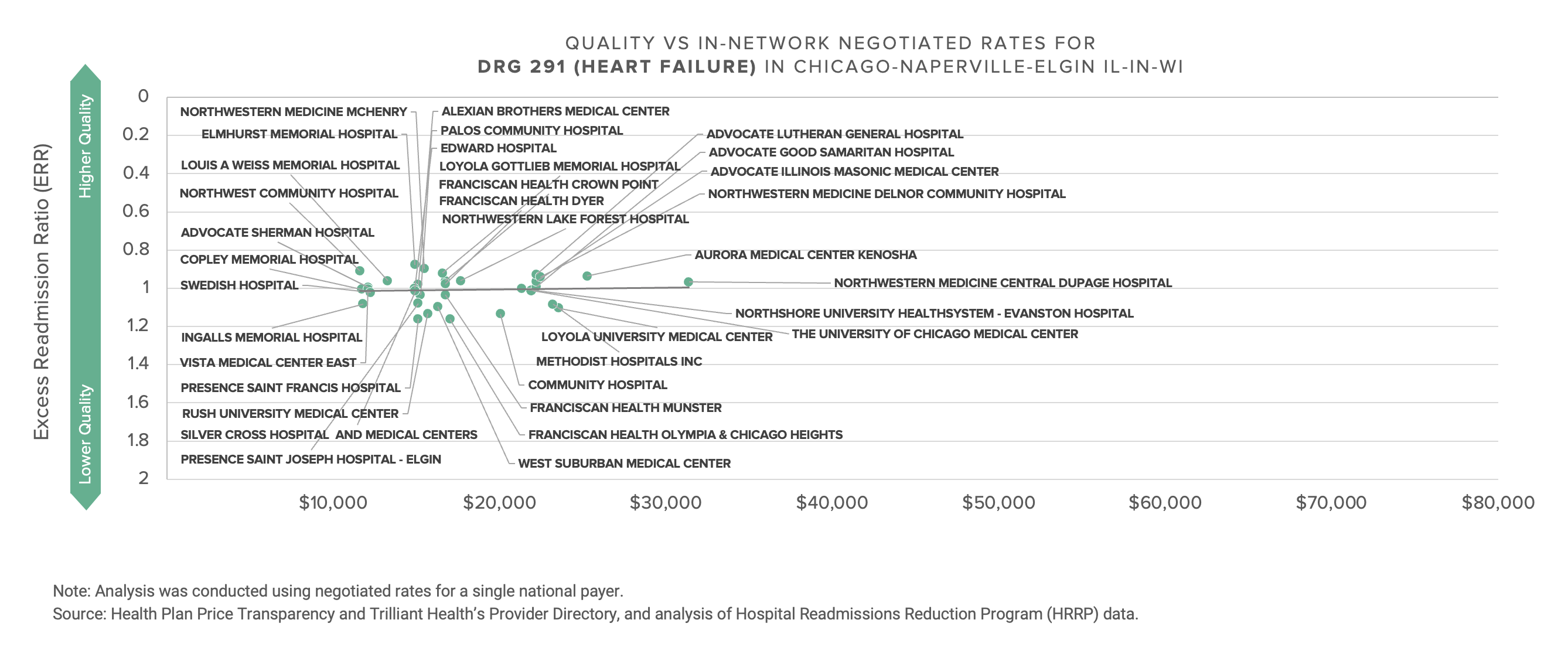

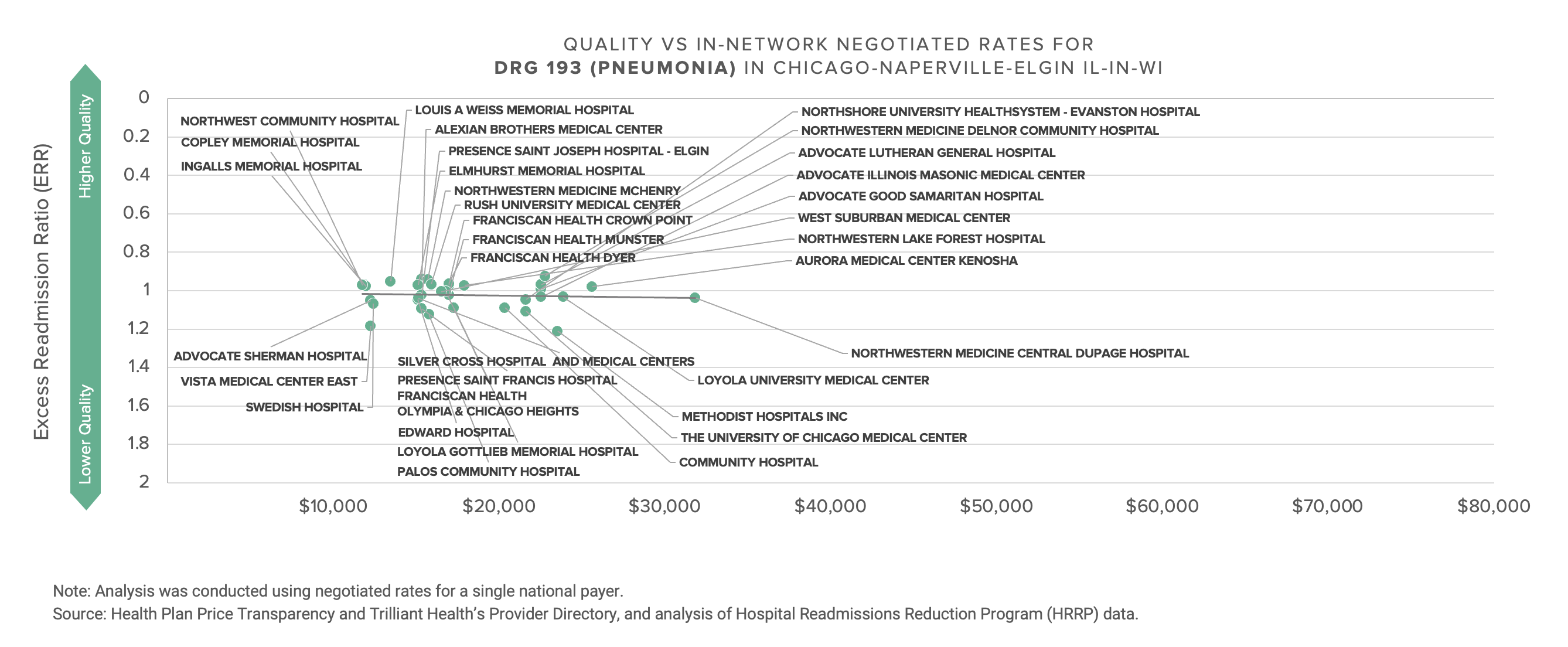

There is almost no (positive) correlation between negotiated price, i.e., what providers receive, and quality, as defined by CMS.

The graphs below compare the negotiated rate paid by UnitedHealthcare for five common DRGs to more than 1,200 hospitals.

With the possible exception of the energy industry, no industry talks more about innovation and transformation than healthcare, and no industry has less to show for the talk. If what’s past is prologue, the response of health economy stakeholders to this data will be denial, followed by more denial, followed by hollow rationalization. With that in mind, I thought focusing on a single market might prompt reflection.

This data presents a Goldilocks dilemma for every health economy stakeholder, whether in Chicago or elsewhere: Can you defend the rate you are receiving or paying?

Providers with premium rates must explain the rationale for receiving Lamborghini rates for Buick quality; likewise, providers with inferior rates must explain to their Board their inability to obtain market rates for delivering equivalent or better quality of services than those provided by the competition. Every commercial payer must explain the extraordinarily wide range of rates they pay for the same quality of services, as well as the premium rates they pay for worse quality. Note that next month’s Counterpoint will explore whether that range is attributable to the supposed market power of dominant health systems, as industry pundits and the Federal government claim, or rather to poor execution – or lack of incentive – by payers.

Other parts of the U.S. economy have been forced to adapt to price transparency and, in turn, price discovery, with Wall Street as a compelling example. For two centuries, stocks traded on the New York Stock Exchange were priced in eighths of a dollar. Why?

“In Spain in the 1600s, Spanish investors traded with gold doubloons, which were split in half, quarter or even one-eighth pieces so traders could count them on their fingers—while skipping their thumbs.”1

What forced the NYSE and other exchanges to begin trading stocks in decimals – and thereby dramatically and permanently changing the price spread – was a mandate by the Securities and Exchange Commission in July 2000.2

The American Hospital Association was forced to use the Danish concrete case as the foundation of its opposition to price transparency because there are not any good examples in American history of universal price increases following price transparency and, in turn, price discovery. In fact, the opposite usually happens, as once-dominant business models and brands are forced to adapt or go bankrupt in response to price transparency, which leads to price discovery, which leads to a reduction in price spreads and revelation of a “market price.” The advent of trading stocks in decimals paved the way for E-Trade and Robinhood; deregulation of the airline industry paved the way for numerous discount airlines and businesses like Priceline and Kayak; the development of the Internet browser allowed Kelley Blue Book to become the most visited automotive site on the Internet in 1995, radically changing the nature of automobile sales.

Health plan price transparency reveals a startling spread in pricing for healthcare services that begs for explanation, not rationalization or justification. As a result, health plan price transparency should inaugurate an era of unprecedented and frenzied competition to win the hearts and minds of the payer that keeps the current U.S. healthcare system afloat: the employer. If it does, the winners in healthcare’s negative sum game will be those who deliver value for money.

Neither Medicare Advantage nor “value-based care” nor direct contracting deliver value for money to the ultimate payer, whether employers or the Federal government. Medicare Advantage is merely risk allocation from the Federal government to health plans; value-based care is risk allocation from the Federal government or health plans to providers, with the occasional side effect of significant redistribution of those fixed dollars from specialty care to primary care; direct to employer is merely elimination of friction cost without meaningful change in the total cost of care.

Whether you are a benefits broker, a health plan, a provider, a life sciences company or (gulp) a pharmacy benefits manager, can you defend your rate? Whoever is first to tell employers the truth might receive amnesty. In the words of Ricky Bobby, “if you ain’t first, you’re last.”

.png)

.png?width=171&height=239&name=2025%20Trends%20Report%20Nav%20(1).png)